to the river with this thunderous me

—“Rainwater From Certain Enchanted Streams”

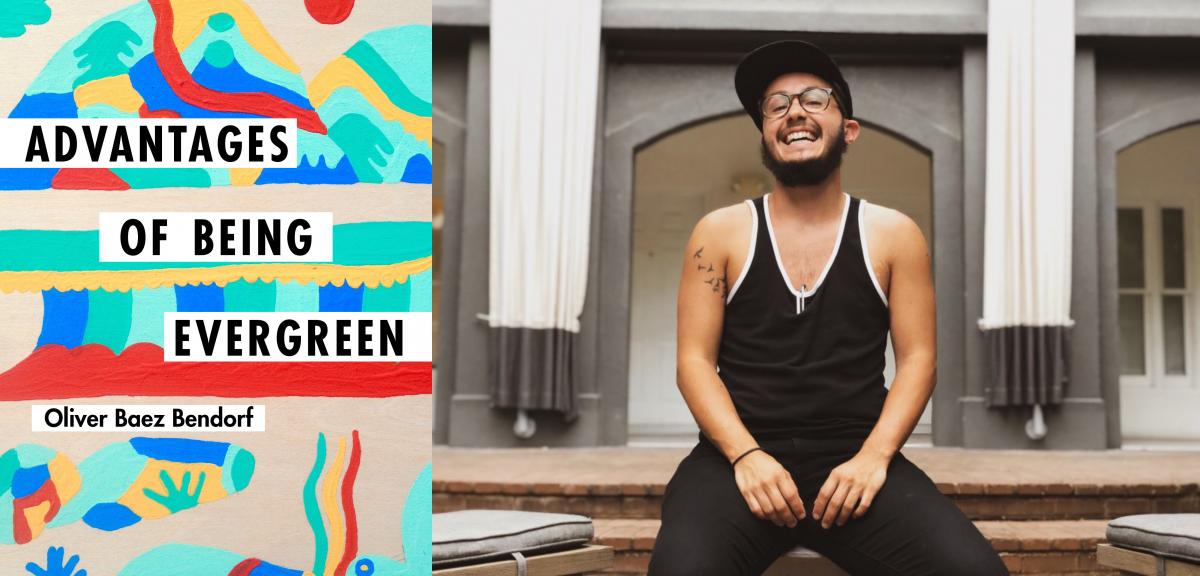

Winner of the 2018 Cleveland State University Open Book Competition, Advantages of Being Evergreen is Oliver Baez Bendorf’s second full-length book of poetry. Released September 2019, this book is a soft, powerful, seasonal-transition kind-of-read.

Evergreen: not limited, eternal growth. This concept of limitlessness floats throughout these pages. In Advantages of Being Evergreen, Bendorf takes us to the river. The river: a space both holding the potential for danger and for sanctuary. The river: both fierce and gentle. The river seems to be both a central place and a central character in the collection. And as the book progresses, there seems to be a shift in the way the river is represented. In the book’s second poem, “Evergreen,” the river has a potential to control life: “when the river rock is done/ with me, I could belong to the evergreen.” Yet, 30 pages later in “River I Dream About,” the river is a sanctuary space, a home. That duality, that multiplicity, that shift feels important in this collection.

In “Rainwater From Certain Enchanted Streams” Bendorf writes, “Some friends call me fairy, dyke, & I’m all these things.” This book is interested in vastness and multitude. It explores the spirit of and relationship between strength and tenderness. The final couplet of a later poem reads, “What I want from the river is what I always want:/ to be held by a stronger thing that, in the end, chooses mercy.” Throughout, there also seems to be an exploration of identity and the way beings hold abundance in one space, in one body. Again, Evergreen: limitlessness. There are poems like “My Body The Haunted House” with lines like “I carry your body (in/ my body). I live for both of us now.” Followed by the stilling fragment, “Cannot pinpoint what I miss,” which resonates and speaks both specifically and universally. How accurate—how we often find ourselves lacking clarity and how that is part of this human experience.

Some poems have the “feels” of confessional poets past, but with an O’Hara-esque immediacy, intimacy, and inviting yet withholding-ness. Specific names are dropped. Bendorf engages the reader, including phrases like: “know what I mean?” and “you know?” There is a group or collective “we” who feels the same in some poems and perhaps shifts in others—lines like “we took family portraits wearing animal masks” and later in the same poem “So many gay bodies on fire, offerings to/ gods who don’t deserve us.” This idea of connection and collective is also at the heart of this book. Though the lines above may not directly speak to the 2016 Ghost Ship tragedy, a number of poems in this book mourn that massive loss.

You will find in these pages, stellar lines and compelling phrasing. Like, “The land in the holler weeps” in the poem “Rain and Ticks in Tennessee.” A line like this gives nature agency, which seems to be another common theme in the collection. You will also find some powerful line breaks, like the stand alone line “scars where my breasts” existing on its own as a one-line stanza asking us to pause on that phrasing.

Stylistically, there is attention to line, language, and voice in every poem. I am particularly drawn to the use of language when Bendorf changes the form and function of words from line to line—because, after all, words can function fluidly. Like in the poem “River I Dream About” when the word “river” shifts from noun to verb and back again: “We pull the river into our bellies” and then “we river in darkness.” This gets at that both/and-ness we see thematically in the collection. A flexibility, a fullness that is embodied in language and in self.

And then you get moments of heat and desire. And one such poem is “Papi Loves Me Like A Violet, Or A Pinata.” A poem holding a repeated line of “how long I take to open,” which continues another theme in the book of human nature and the natural world bearing all resemblance.

Other poems contain moments that feel like a meditation—an example is in the poem, “I Think I’ve Already Come Back As Something Else” in the lines:

grey herons

coming through an open sky

everything falls away

attention narrows only to sensation

someone cries and someone comes

back and someone else eats

part of a partly rotten apple.

This book is, I believe, in part, about connection—to nature, to self, to body, to a collective. The speaker takes us on a journey through nature, through states, through internal states, and I think we see in the end: connection is what sustains.

Oliver Baez Bendorf is the author of a previous collection, The Spectral Wilderness, selected by Mark Doty for the Stan & Tom Wick Poetry Prize, and a chapbook, The Gospel According to X. He is an assistant professor of poetry at Kalamazoo College in Michigan.

Holly Mason received her MFA in Poetry from George Mason University, where she taught undergraduate courses and served as the blog editor for So to Speak: A Feminist Journal of Language and Art. Her poems have appeared in Rabbit Catastrophe Review, Outlook Springs, The Northern Virginia Review, Bourgeon, and Foothill Poetry Journal. She received a Bethesda Urban Partnership Poetry prize, selected by E. Ethelbert Miller. She has been a reader and panelist for OutWrite (A Celebration of Queer Literature) in D.C. and currently lives in Northern Virginia.